Horses

“The

governor then gave the signal to Candia, who began to fire off the guns.

At the same time the trumpets were sounded, and the armored Spanish troops, both

cavalry and infantry, sallied forth out of their hiding places straight into the

mass of unarmed Indians crowding the square, giving the Spanish battle cry,

‘Santiago!’ We had placed rattles on the horses to terrify the

Indians. The booming of the guns, the blowing of the trumpets, and the

rattles on the horses threw the Indians into panicked confusion. The

Spaniards fell upon them and began to cut them to pieces. The Indians were

so filled with fear that they climbed on top of one another, formed mounds, and

suffocated each other. Since they were unarmed, they were attacked without

danger to any Christian. The calvary rode them down, killing and wounding,

and following in pursuit. The infantry made so good an assault on those

that remained that in a short time most of them were put to the

sword…

The panic-stricken Indians

remaining in the square, terrified at the firing of the guns and at the horses –

something they had never seen – tried to flee from the square by knocking down a

stretch of wall and running out onto the plain outside. Our calvary jumped

the broken wall and charged into the plain, shouting, ‘Chase those with the

fancy clothes! Don’t let any escape! Spear

them!’”

eyewitness account from Guns,

Germs, and Steel page 73

One of the more obvious

anachronisms contained in the Book of Mormon is the presence of horses.

There are many other anachronistic plants and animals present in the Book of

Mormon, such as wheat, cattle, ox, sheep, elephant and the ass. I consider

the horse the most interesting of these anachronisms, due to the impact of the

horse on societies that actually possess them.

For reference, the following are

the horse verses from the Book of Mormon.

1

Ne. 18:25 And it came to pass that we did find upon the land of promise, as we

journeyed in the wilderness, that there were beasts in the forests of every

kind, both the cow and the ox, and the ass and the horse, and the goat and the

wild goat, and all manner of wild animals, which were for the use of men. And

we did find all manner of ore, both of gold, and of

silver, and of copper.

2 Ne. 12:7 Their land also is full of silver and

gold, neither is there any end of their treasures; their land is also full of

horses, neither is there any end of their chariots. (Isaiah verse - not

relevant to horses in the New World)

2 Ne. 15:28 Whose arrows shall

be sharp, and all their bows bent, and their horses’ hoofs shall be counted like

flint, and their wheels like a whirlwind, their roaring like a lion.

(Isaiah verse - not relevant to horses in the New World)

Enos 1:21

And it came to pass that the people of Nephi did till the land, and raise all

manner of grain, and of fruit, and flocks of herds, and flocks of all manner of

cattle of every kind, and goats, and wild goats, and also many

horses.

Alma 18:9 And they said unto him: Behold, he is feeding thy

horses. Now the king had commanded his servants, previous to the time of the

watering of their flocks, that they should prepare his horses and chariots, and

conduct him forth to the land of Nephi; for there had been a great feast

appointed at the land of Nephi, by the father of Lamoni, who was king over all

the land.

Alma 18:10 Now when king Lamoni heard that Ammon was preparing

his horses and his chariots he was more astonished, because of the faithfulness

of Ammon, saying: Surely there has not been any servant among all my servants

that has been so faithful as this man; for even he doth remember all my

commandments to execute them.

Alma 18:12 And it came to pass that when

Ammon had made ready the horses and the chariots for the king and his servants,

he went in unto the king, and he saw that the countenance of the king was

changed; therefore he was about to return out of his presence.

Alma

20:6 Now when Lamoni had heard this he caused that his servants should make

ready his horses and his chariots.

3 Ne. 3:22 And it came to pass in the

seventeenth year, in the latter end of the year, the proclamation of Lachoneus

had gone forth throughout all the face of the land, and they had taken their

horses, and their chariots, and their cattle, and all their flocks, and their

herds, and their grain, and all their substance, and did march forth by

thousands and by tens of thousands, until they had all gone forth to the place

which had been appointed that they should gather themselves together, to defend

themselves against their enemies.

3 Ne. 4:4 Therefore, there was no

chance for the robbers to plunder and to obtain food, save it were to come up in

open battle against the Nephites; and the Nephites being in one body, and having

so great a number, and having reserved for themselves provisions, and horses and

cattle, and flocks of every kind, that they might subsist for the space of seven

years, in the which time they did hope to destroy the robbers from off the face

of the land; and thus the eighteenth year did pass

away.

3 Ne. 6:1 And now it came to pass

that the people of the Nephites did all return to their own lands in the twenty

and sixth year, every man, with his family, his flocks and his herds, his horses

and his cattle, and all things whatsoever did belong unto them.

3 Ne.

21:14 Yea, wo be unto the Gentiles except they repent; for it shall come to pass

in that day, saith the Father, that I will cut off thy horses out of the midst

of thee, and I will destroy thy chariots;

Ether 9:19 And they also had

horses, and asses, and there were elephants and cureloms and cumoms; all of

which were useful unto man, and more especially the elephants and cureloms and

cumoms.

Book of Mormon scholars concede that

there is no evidence of the existence of the horse in the New World during the

specified Book of Mormon time period, although some hint at some future

supporting evidence yet to appear, or the possible development of dated

references.

Given

the fact that schoolchildren in the United States have long been taught that the

Europeans introduced horses to the New World, it seems surprising that so many

believing LDS read these passages in the Book of Mormon without protest or

question. In my opinion, this is likely due to the fact that human beings

rely on a different part of their brain in religious contexts than they do in

other non-religious contexts. It just doesn’t “connect”. Moreover,

this flaw did not “connect” with other nineteenth century authors, either.

Solomon Spalding, in Manuscript Story, mentions horses in connection with

the inhabitants of the New World.

"Corn,

wheat, beans, squashes, & carrots they raised in great abundance. The ground

was plowed by horses & generally made very mellow for the reception of the

seed.” (chapter V)

“As the whole of this parade

indicates no flight of Elseon & Lamesa, we might now view them, with their

select company of friends setting out on a short journey. All mounted on horses,

they rode about twenty miles to a village were they halted. An elegant supper

was provided. They were cheerful & sociable, none appeared more so than

Elseon & Lamesa. The next day Elseon requested the company of his dear

cousins a short distance on his journey. When they had rode about two miles they

halted & proposed to take their leave of each other. Lamesa & her friend

without being perceived by the company rode on. It was a place where the road

turned & by riding one rod they could not be seen. The rest of the company

entered into a short conversation & passed invitations for reciprocal visits

& friendly office. They then clasped each others hands, & bowing very

low took an affectionate farewell. But where are Lamesa & her friend? During

these ceremonies their horses moved with uncommon swiftness, her heart

palpitates with an apprehension that she might be overtaken by her brother. But

now a friend more dear, her beloved Elseon, with his companions, outstrip the

wind in their speed, & within one hour & half they overtake these

fearful damsels. They all precipitate their course casting their eyes back every

moment to her pursuers.” (chapter XI)

Part of the difficulty is that the

fact that the Native Americans soon adopted and adapted their entire culture to

the horse, once it was, in fact, introduced by the Europeans. The Indian

and his horse is so embedded in our conceptions of Indians that it is a

challenge to extricate the two.

Diamond emphasizes this fact, on

page 75.

“The

sole Native Americans able to resist European conquest for many centuries were

those tribes that reduced the military disparity by acquiring and mastering both

horses and guns. To the average white American, the word “Indian” conjures

up an image of a mounted Plains Indian brandishing a rifle, like the Sioux

warriors who annihilated General George Custer’s US Army battalion at the famous

battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. We easily forget that horses and

rifles were originally unknown to Native Americans. They were brought by

Europeans and proceeded to transform the societies of Indian tribes that

acquired them. Thanks to their mastery of horses and rifles, the Plains

Indians of North America, the Araucanian Indians of southern Chile, and the

Pampas Indians of Argentina fought off invading whites longer than did any other

Native Americans, succumbing only to massive army operations by white

governments in the 1870s and 1880s.”

Despite the firm modern association of

the horse to the Native American, it is universally accepted among mainstream

archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians that there is no evidence of the

existence of a pre-Columbian horse, excepting the long-extinct species. How have

they arrived at this conclusion?

There are several ways that scientists can fairly

accurately ascertain the existence of past animals. The easiest method is,

of course, through fossilized remains and bone remnants. Horses are one of

the best candidates. From Horses Through Time, published by

the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, edited by Sandra L. Olsen, page

13:

“

Among mammals horses are classified with the ungulates, the

great group of large-bodied herbivores (plant eaters). Other living

ungulates include the rhinoceroses, camels, deer, antelope, cattle, elephants,

and manatees. The combination of ungulates’ large,

sturdy bones and teeth and their great abundance in most faunas leads to their

having an excellent and relatively complete fossil record. The horse

family, Equidae, is no exception to this generalization. Many tens of

thousands of specimens of equid fossils have been discovered in North America,

Eurasia, Africa, and to a lesser degree, South America. These range from

very rare complete skeletons to isolated bones and teeth, the most common

finds.

Paleontologists have been analyzing the

equid fossil record for well over 150 years, continually making new discoveries,

describing new species, reinterpreting old data, and in general learning more

about the evolution, anatomy, and ecology of this group. For example,

paleontologists named an average of three new species of horses between 1973 and

1987. Many paleontologic interpretations are controversial, with

contending or alternative hypotheses and theories held by different

specialists. As new specimens are found and more data accumulate, some of

these ideas are proven unlikely, whereas others are corroborated or totally new

hypotheses are proposed. By this method paleontologists progressively gain

greater understanding of the evolutionary history of the horse, as well as other

organisms.

The fossil record of the horse has an

important role in the history of science, in particular the study of biologic

evolution. In the late 1800s horses became the first group of mammals that

paleontologists could place in a reasonably plausible sequence of ancestors and

descendants from a living species back to the beginning of the Age of Mammals,

65 million years ago. Although we now know this sequence was grossly

oversimplified, incomplete, and in places simply wrong, it was still an

important achievement for the time. With the wide availability of fossil

specimens, most natural history museums had the resources to display an exhibit

on the evolution of the horse and scores of biology and geology textbooks used

the horse as an example for an evolutionary sequence.”

Using such fossils, scientists have,

indeed, constructed a timeline for the existence of and subsequent extinction of

the horse species in the American continent.

“Without

getting into details, which are murky to begin with, starting in the very late

Pliocene, about 2.5 million years ago, most North American fossil faunas

contained two to four species of Equus. Often there was a small,

pony-sized type coexisting with a larger form, both with relatively stout

limbs. An additional, very slender-legged, usually medium-sized species

probably related to the Asiatic asses was occasionally present as well,

especially in the early and middle Pleistocene. There are more Pleistocene

fossil localities than from any other age, because this period is the most

recent, and Equus is common in almost every locality that contains large

mammals. This situation continued until near the end of the Pleistocene,

about 11,000 years ago, when many North American mammals became extinct over a

short period of time. Victims of this mass extinction event included

mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, camels, tapirs, and horses among the large

herbivores as well as the large carnivores that preyed upon them, such as lions,

saber-toothed cats, and dire wolves. There is an ongoing controversy as to

the immediate cause of this event, with rapid climatic and ensuing vegetational

change, and overhunting by humans being the two opposing views. In either

case the 57-million –year history of the horse in North America came to an end,

at least until the introduction of domesticated horses and donkeys by European

explorers and colonists.

North American Equus also

dispersed to other continents. It first appeared in South America in the

middle Pleistocene and successfully spread throughout the continent. There

it coexisted with Hippidion and Onohippidium until the end of the

Pleistocene. Then, as in North America, all South American horses became

extinct.” (page 31)

Admittedly some climates are more conducive to the

preservation of animal bones than others. Mesoamerica, while not the best

climate for such preservation, does, indeed, offer many examples of other animal

bones. In fact, there is an abundance of animal bones in Mesoamerica, even

from the Pleistocene era. The following are just a few of many references

to excavated bones in Mesoamerica.

“Somewhat

less equivocal evidence from Tlapacoya relates to a later tradition, resembling

more closely that of early Valsequillo. The Tlapacoya data result from

eight seasons of interdisciplinary fieldwork carried about between 1965 and 1973

under the principal direction of J. L. Lorenzo and L. Mirambell. In

addition to the artifactual remains reported from the excavations, analyses of

the local geology, limnology,

pollen, and fauna were included in

their study. A suite of radiocarbon dates was obtained, seventeen of which

fall between 33,000 and 14,000 years b.p. The investigators accept as

representative a determination of 21,700 +/- 500 years b.p. on carbon and soil

from a circular hearth, about 1.15 meters in diameter, within and adjacent to

which were found stone tools and abundant animal bones, many from now extinct

Pleistocene mammals. Two other cooking areas, one radiocarbon dated at

24,000 +/- 4000 years b.p., provide addition evidence for what appears to be a

series of temporary campsites along the ancient Chalco lakeshore.”

The Cambridge History of the

Native Peoples of the Americas: Volume 2, Mesoamerica, Part 1, by Richard E

Adams, page 43.

The same book also discusses

animal bones found of Teotihuacan date that included rabbit, hare, and deer

bones. (page 91) Also, on page 222, the author demonstrates that

scarcity of animal bones is evidence that animals did not play a large part in

the diet of the particular group, rather than evidence that the climate would

not allow preservation of such bones, as is sometimes claimed by certain Book of

Mormon scholars.

Sometimes animal bones are not

simply part of household refuse, but are rather evidence of religious rituals

such as sacrifice. In Ancient Maya Commoners, edited by Jon C.

Lohse and Fred Valdez, Jr. Marilyn A. Masson and Carlos Peraza Lope’s essay

Commoners in Postclassic Maya Society: Social Versus Economic Class

Constructs, page 206, we read:

“The

inventory of elite residential structure I is otherwise quite similar to all

other domestic zones tested on the island and shore, with the exception of

marine shell debris, which is more abundant than at other contexts. The

limited distributions of ritual artifacts (including sacrificed animal remains)

and shrine structures distinguish a potential social class of elites at Laguna

de On from other family groups.”

Decorated

Bone

While, at times, Book of Mormon scholars claim that

the damp Mesoamerican climate and the acidic soil explain why there could have

been horses who left no remains, (see “Horses in the Book of Mormon”, a FARMS

report), this does not stop them from attempting to locate such evidence,

nonetheless. John Sorenson offered a controversial reference for such

remains, which was then analyzed in The Quest for Gold Plates, by Stan

Larson, page 190:

“Sorenson,

in an effort to support his position that the horse might have survived into

Book of Mormon times, stated the following:

Pleistocene fauna could not have

survived as late as 2000 BC. Dr. Ripley Bullen thought horses could have

lasted until 3000 BC in Florida, and JJ Hester granted a possible 4000 BC

survival date.

Let us examine Sorenson’s three

assertions. (1)Paul S. Martin, professor of geosciences at the University

of Arizona, was quoted out of context, for after expressing the theoretical

possibility that Sorenson referred to, Martin then made the following

strong statement: “But in the past two decades concordant stratigraphic,

palynological [relating to the study of pollen], archaeological, and radiocarbon

evidence to demonstrate beyond doubt the post-glacial survival of an extinct

large mammal has been confined to extinct species of Bison.” (2)Ripley

Bullen spoke in general of the extinction of mammals in Florida and not

specifically of the horse as Sorenson asserted. (3)James J. Hester,

professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado, did not suggest that

the horse survived until 4000 BC, but rather used a date more than two thousand

years earlier. Hester’s date of 8240 years before the present (with a

variance of +- 960 years) was published in 1967, but the validity of the

radiocarbon dating for these horse remains at whitewater Draw, Arizona, has been

questioned. The next youngest horse of 10,370 +- 350 years ago has a

better quality of material being dated and stronger association between the

material actually being tested and the extinct genus. Clearly, Sorenson’s

three arguments for a late survival of the horse do not hold up under

scrutiny. Certain now extinct species may have survived in particular

areas after the Ice Age. For example, one scholar recently stated that “in

one locality in Alberta, Equus conversidens [a short-legged, small horse] may

have been in existence about 8,000 BP (Before Present). While there may

have been small “pockets” of horses surviving after the Late Pleistocene

extinctions, the time period for such survivals would still be long before the

earliest Jaredites of the Book of Mormon.

John W. Welch, professor of law at

BYU, referred to the find in Mayapan or horse remains which were “considered by

the zoologist studying them to be pre-Columbian.” Examination of Welch’s

citation reveals that he misinterpreted the evidence, which does not date to pre

Columbian times (and hence potentially to the BoM period) but rather to

prehistoric Pleistocene times. This find at Cenote Ch’en Mul consists of

one complete horse tooth and fragments of three others, which were found six

feet below the surface in black earth and were “heavily mineralized

(fossilized), unlike any other material in the collections.” Thousands of

bones and teeth were examined at Mayapan, which is a Late Post Classic site

established in the thirteenth century AD, but these four horse teeth were the

only ones fossilized. The reporting scholar did not suggest that the Mayan

people hade ever seen a pre-Columbian horse, but that in Pleistocene times

horses lived in Yucatan, and that “the tooth fragments reported here could have

been transported in fossil condition by the Maya as curiosities. Thus,

Welch’s assertion about pre-Columbian horses must be corrected to refer to

ancient Pleistocene horses, since these fossilized horse teeth at Mayapan date

to thousands of years before the Jaredites.” (p. 190-191)

Updated

Information:

The Alberta remains' dating has

been corrected. The following information is obtained from an abstract for

an article called "New Radiocarbon Dates for Columbian Mammoth and Mexican horse

from Southern Alberta and the Late Glacial Regional Fauna":

New

radiocarbon dates on Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) and Mexican horse

(Equus conversidens) specimens from southern Alberta are 10,930±100 BP and

10,870±45 years BP, respectively—older than originally thought. These specimens

are reviewed in the light of 10 other sites in southern Alberta that have

yielded large mammal remains radiocarbon dated to about 11,000 BP. Thus, the

regional fauna includes at least 11 mammalian species. This fauna was not

restricted to the foothills, but extended well onto the plains and may prove

useful in correlating foothills terraces with those of the plains.

The

article most often cited to support Sorenson's assertion is a 1956 article from

the Museum of Comparative Zoology by Clayton C. Ray. This article cannot

be accessed online, but Chris Smith obtained and scanned it.

The

remains of horses have been reported from cave deposits in the state of Yucatan,

Mexico, on two previous occasions. Mercer (THE HILL CAVES OF YUCATAN,

LIPPINCOTT, PHILA., 1896, p. 1972 and map opposite title page) found horse

remains in three caves in the Serrania, a low range of limestone hills lying in

southwestern Yucatan and trending roughly parallel to the southwest border of

that state. The horse material was associated with pot sherds and other

artifacts and showed no evidence of fossilization. Cope (in Mercer

op. cit. p. 172, footnote) examined the material and considered it referable to

Equus occidentalis on morphological characteristics but noted absence of

fossilization.

Hatt records numerous fragments of

Equus ?conservidens from Actun Lara, one of Mercer’s caves, (1953,

Cranbrook Inst. Sci., Bull. 33, pp. 71-72 and map 2). These remains

were tentatively referred to Equus tau by R. A. Stirton (in Hatt, p.

71). Hibbard regards E. tau as probably synonymous with E.

conservidens (1955, Contrib., Mus. Paleo. Univ. Mich.,12:61).

Although the teeth and bones were in many cases heavily encased in lime, pottery

occurred throughout the deposits and two foot bones present in the upper layer

of two layers in which horse remains occurred were identified as those of

domestic cattle.

It is now possible to report horse

remains of probably pre-Columbian age from a new locality in Yucatan. This

material consists of one complete upper molar and 3 fragmentary lower molars,

all preserved in the Museum of Comparative Zoology (Cat. No 3937), The

teeth constitute a part of a large collection of vertebrate remains obtained by

archaeologists of the Carnegie Institution of Washington during excavation at

the Mayan ruins of Mayapan, Yucatan (20,38N,89,28W). This collection was

submitted to the author for identification, and a checklist of the material is

in preparation. The horse teeth were collected in cenote Ch’en Mul (Section Q,

topographic map of the ruins of Mayapan, Jones, Carnegie Inst. Washington, Dept.

Archaeology, Current Rept. 1, 1952) from the bottom stratum in a sequence of

unconsolidated earth almost 2 meters in thickness. As in the deposits reported

by Mercer and Hatt, pottery occurs throughout the stratigraphic section.

The horse teeth are not specifically identifiable. They are considered to be

pre-Columbian on the basis of depth of burial and degree of mineralization. Such

mineralization was observed in no other bone or tooth in the collection although

thousands were examined, some of which were found in close proximity to the

horse teeth.

It is by no means implied that

pre-Columbian horses were known to the Mayans, but it seems likely that horses

were present on the Yucatan Peninsula in pre-Mayan time. The tooth

fragments reported here could have been transported in fossil condition as

curios by the Mayans, but the more numerous horse remains reported by Hatt and

Mercer (if truly pre-Columbian) could scarcely be explained in this manner.

CLAYTON C. RAY, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Mass. Received May

28,1956).

Additional information is

available to evaluate these original dated findings. The book "Ice Age

Faunas of North America" has certain pages available on a google book search,

and several of these pages address this event.

Henry

C. Mercer (1896), who explored the cave and dug 2 pits in Chamber 3 in 1895,

found similar ceramic and nonceramic layers. His attempt to locate

preceramic artifacts with extinct fauna in association with Loltun or other

nearby caves was unsuccessful. Some skeletal remains dubiously identified as

Ursus (bear) were found in Loltun in a ceramic layer. Mercer reported the

presence of Equus (horse) teeth and bones on the surface of three different

caves. Although similar to the extinct horse Equus Occidentalis, the

remains were identified as modern horse. Cope (1896) studied the remains of

other animals collected by Mercer in Loltun, including species of

opossums, bats, rabbit, mice, peccary, and deer if two sizes (page

263)

The same text also addresses the

Hatt findings.

The

most extensive study of the region was undertaken by Mr. and Mrs. Robert T.

Hatt, who in 1929 and 1947 explored fourteen “cenotes” and dug in nine of them.

(Hatt et al 1953). Two cenotes near Loltun contained the remains of

extinct animals. Pleistocence Equus conversidens was recovered from Actun

Lara. Actun Spukil produced a left tympanic ring and a molar fragment from

the ground sloth, Paramylodon. In all, Hatt et al. (1953) collected

forty-five species of mammals, of which six had been introduced by the

Spaniards.

The Hatts

collected only on the surface and in the top 10 cm of sediments in Chamber 3 in

Loltun Cave (Hatt et al. 1953). Although further excavations were not

pursued, the Hatts did recover twenty four mammal species, five of which were

introduced (Mus Musculus, Canis familiaris, Equus axinus, Capra Hircus, and Bos

Taurus). Native species represented two marsupials, one insectivore, four

bats, one lagomorph, nine rodents, one carnivore, and one artiodactyls (Table

10.1). Hatt et al. (1953) indicated in their final report that the Loltun

Cave was the most promising archaeological site for obtaining clues to the

cultural and faunal changes since the end of the Pleistocene. (page

263)

This reference clarifies that the

horse remains were from the Pleistocene Era, which ends around 11,550 years

before present.

A summary of the animal remains in

the Loltun Cave was also provided.

The

time range represented is from over 28,400 yr BP. Not all taxa are found

throughout this long period, but they can be divided into three main groups

(Table 10.3). Group I (Holocene and Pleistocene) is formed by those species that

occur through most of the stratigraphic sequence, accounting for more than half

of the identified of the identified species (n = 39, 57.3 percent). Group

2 (n = 18 species, 26.5 percent) is composed of those species found only in the

Holocene sediments. Species that occurred only in the Pleistocene strata

constitute Group 3.

Table 10.3 Mammal Species

from Loltun Cave Divided According to Their Temporal Record in the

Excavation.

Group 1- Holocene and Pleistocene

Didelphis marsupialis, Marmosa

canescens,M. Mexicana, Cryptotis, Cryptotis mayensis, Peropteryx macrotis,

Pteronotus parnellii, Mormoops megalophylla, Chrotopterus auritus, Glossophaga

soricina, Stumira lilium, Artibeus jamaicensis, hiroderma villosum, Desmodus

rotundus, Diphylla ecaudata,Eptesicus furinalis, Lasiurus ega I. Intermedius,

Nyctinomops laticaudatus, Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Leopardus pardalis, L.

wiedii, Puma concolor, Panthera onca, Conepatus semistriatus, Spilogale

putorius, Nasua narica, Mazama sp, Odocoileus virginiamus, Pecari tajacu,

Sciurus deppei, S. yucatanemis, Orthogeomys hispidus, Heteromys gaumeri,

Oryzomys couesi, Ototylomys phyllotis, Peromyscus leucopus, P. yucatanicus,

Sigmodon hispidus, Sylvilagus floridanus.

Group 2 – Holocene Only

Philander opposum, Pteronotus

davyi, Carollia brevicauda, Centurio senex, Natalus stramineus, Myotis keaysi,

Eumops bonariensis, E. underwoodi, Promops centralis, Molossus rufus, Dasypus

novemcinctus, Canis familiaris, Urocyon cinereoargenteus, Bassariscus

sumichrasti, Procyon lotor, Mustela frenata, Coendou mexicanus, agouti

paca

Group 3 – Pleistocene Only

Marmosa lorenzoi, desmodus

cf. D draculae, Canis dirus, C. latrans, C. lupus, mephitis sp, Cuvieronius sp,

Equus Conversidens, Bison sp, Hemiauchenia sp, Sylvilagus brasiliensis

page 267

Note that Equus Conversidens is

listed as ONLY Pleistocene. The Bison reference is to a now extinct species that

was extanct during the Pleistocene era. This is likely what Mercer

originally thought were "cattle" bones.

Now, where were the Pleistocene

animal remains found? The next citation makes it very

clear:

The

Pleistocene mammal fauna from Loltun Cave consist of those remains from the

bottom of Level VII downward and is represented by fifty species (Groups 1 and

3) in forty genera, twenty-three families, and nine orders. This variety

is one of the largest from the late Pleistocene of Mexico (Arroyo-Cabrales et

al, in press; Kurten and Anderson 1981). Furthermore, it is the most

diverse fossil mammal fauna for the Neotropical region of North and

CentralAmerica (Fernasquia-Villafranca 1978; Webb and Perrigo 1984).

page 268

There was only one citation that

made the dating of the horse bones seem questionable, and it certainly wasn’t

placing them up in level V. This citation does not contradict the previous

one, because we already know the scientists say that the demarcation between the

Pleistocene era and the Holocene era could be in the bottom of Level VII.

This would be around 9,500 BC.

To

date, a comprehensive publication on the site has not been produced; however,

several studies have reported on some of the important findings from the

excavations by INAH. These findings include layers with ceramics and

lithics, and layers with only lithics in association with extinct animals.

These ceramic lithic layers are important for assessing the purpose and

lifestyle of the first human beings that occupied the Yucatan Peninsula.

Other studies cover lithic morphology and typology (Konieczna 1981), and

biological remains, such as mammal bones (Alvarez and Polaco 1972; Alvarez and

Arroyo-Cabrales 1990; Arroyo-Cabrales and Alvarez 1990), mollusk shells (Alvarez

and Polaco 1972), and plants (Montufar 1987; Xelhuanzi-Lopex 1986).

It is clear that

Loltun Cave is an important site because of the presence of lithic tools and

Pleistocene fauna, though doubts still exist about the stratigraphic and

temporal associations. The presence of Pleistocene Equus conversidens in

ceramic layers has been interpreted as possible proof of the survival of the

extinct horse into the Holocene (Schdmit 1988)

page 264

Level VII is a ceramic level, and

we already know that the animals were at the bottom of Level VII. There is

uncertainty as to whether the demarcation between the Pleistocene and Holocene

eras would be in Level VIII or at the bottom of Level VII. The rest of the

citations in this book accept the placement of the demarcation in Level

VII.

Now could this be evidence of the

horse in the BoM time period? Nonsense. This is like Sorenson’s

earlier statement that supposedly finding pockets of extinct animals surviving

into 8,000 BC would constitute evidence for the BoM. We are still talking

about many thousands of years prior to the BoM time period.

Yet another citation refers to

this particular find. The following is obtained from the text “The

Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of North America”, page 62, which is

available from a google book search:

Currently,

only one site in Mesoamerica supports the hypothesis of human occupation in

lowland environments before 12,000 years ago. In the Puuc Hills of

northern Yucatan, the lowest levels of excavations reported by R. Velazquez at

Loltun Cave have produced some crude stone and bone tools along with the remains

of horse, mastodon, and other now extinct Pleistocene animals. Felines,

deer, and numerous rodents round out the archaeological assemblage. No

radiocarbon dates have been forthcoming for this proposed early components that

underlies later ceramic occupations. On the basis of stone tool typology and

faunal association, MacNeish has proposed that the lower

levels of Loltun Cave are somewhere between 40,000 and 15,000 years

old.

This citation demonstrates that

the horse remains were identified as extinct Pleistocene animals, and were

located in the lower levels underlying the ceramic levels.

One interesting aspect of these

particular defenses is that they tend to rely on dated references. One

possible reason for this is that the results of radiocarbon dating was less

reliable in its early phase. The following statement by Paul Martin, in an

essay dealing with mammoth extinction, also emphasizes this

point:

Not

since the early years of 14C dating, when laboratory protocols for sample

selection and pretreatment were not standardized or well understood by consumers

of dates (see, e.g., Martin 1958 and Hester 1960), has anyone seriously advanced

the thought that mammoths or mastodons survived into the mid-Holocene. Those

North American Holocene dates of yore were not replicated and could not be

supported stratigraphically and geochemically. They moulder in the graveyard of

unverified measurements.

In addition to the unreliability

of early carbon dating, another problem originates from the excavation of caves

themselves. The abstract for the article Excavations in Footprint Cave, Caves

Branch, Beliz, states the following:

The

use of caves by the ancient Maya has been previously documented, but the nature

of artifact preservation in these caves presents unique problems not encountered

in surface sites of the region. The absence of stratigraphy, though it means

that we can view objects as they were left by the Maya, also means that

perspective can be distorted, for actions that may have taken place over a long

period of time result in an arrangement of objects that appears to us to be

synchronic. The nature of artifact preservation in caves presents another, more

pressing problem: artifacts are accessible and therefore easily stolen. Although

all surface sites in Belize are endangered, cave sites are especially so, and in

recent years theft of artifacts and attendant destruction of sites has

increased. The following is a report of excavations in a cave that is one of

many in an area that has begun to experience the destructive effects of looting

within the last decade. We hope that this report will heighten the awareness of

archaeologists of the significance of cave sites and stimulate interest in the

reconnaissance and recording of such sites before the looters

prevail.

Given these circumstances, it is

understandable that earlier archaeologists may have been confused about their

finds, but these updated sources demonstrate that when these findings are more

thoroughly investigated, the same conclusion is verified: there was no

post-Pleistocene, pre-Conquest horse in the New World.

Sorenson utilized an additional reference.

We can read a reference to it in Daniel Peterson's review of The Quest for Gold

Plates titled "Ein

Heldenleben? On Thomas Stuart Ferguson as an Elias for Cultural Mormons":

Publications

from the late 1950s reported results from excavations by scientists working on

the Yucatan Peninsula. Excavations at the site of Mayapan, which dates to a few

centuries before the Spaniards arrived, yielded horse bones in four spots. (Two

of the lots were from the surface, however, and might represent Spanish horses.)

From another site, the Cenote (water hole) Ch'en Mul, came other traces, this

time from a firm archaeological context. In the bottom stratum in a sequence of

levels of unconsolidated earth almost two meters in thickness, two horse teeth

were found. They were partially mineralized, indicating that they were

definitely ancient and could not have come from any Spanish animal. The

interesting thing is that Maya pottery was also found in the stratified soil

where the teeth were located.

Subsequent digging has

expanded the evidence for an association of humans with horses. But the full

story actually goes back to 1895, when American paleontologist Henry C. Mercer

went to Yucatan hoping to find remains of Ice Age man. He visited 29 caves in

the hill area—the Puuc—of the peninsula and tried stratigraphic excavation in 10

of them. But the results were confused, and he came away disillusioned. He did

find horse bones in three caves (Actun Sayab, Actun Lara, and Chektalen). In

terms of their visible characteristics, those bones should have been classified

as from the Pleistocene American horse species, then called Equus occidentalis

L. However, Mercer decided that since the remains were near the surface, they

must actually be from the modern horse, Equus equus, that the Spaniards had

brought with them to the New World, and so he reported them as such.3

In 1947 Robert T. Hatt repeated Mercer's activities. He found within Actun Lara

and one other cave more remains of the American horse (in his day it was called

Equus conversidens), along with bones of other extinct animals. Hatt recommended

that any future work concentrate on Loltun Cave, where abundant animal and

cultural remains could be seen.

It took until 1977

before that recommendation bore fruit. Two Mexican archaeologists carried out a

project that included a complete survey of the complex system of subterranean

cavities (made by underground water that had dissolved the subsurface

limestone). They also did stratigraphic excavation in areas in the Loltun

complex not previously visited. The pits they excavated revealed a sequence of

16 layers, which they numbered from the surface downward. Bones of extinct

animals (including mammoth) appear in the lowest layers.

Pottery and other

cultural materials were found in levels VII and above. But in some of those

artifact-bearing strata there were horse bones, even in level II. A radiocarbon

date for the beginning of VII turned out to be around 1800 BC. The pottery

fragments above that would place some portions in the range of at least 900–400

BC and possibly later. The report on this work concludes with the observation

that "something went on here that is still difficult to explain." Some

archaeologists have suggested that the horse bones were stirred upward from

lower to higher levels by the action of tunneling rodents, but they admit that

this explanation is not easy to accept. The statement has also been made that

paleontologists will not be pleased at the idea that horses survived to such a

late date as to be involved with civilized or near-civilized people whose

remains are seen in the ceramic-using levels.5

Surprisingly, the Mexican researchers show no awareness of the horse teeth

discovered in 1957 by Carnegie Institution scientists Pollock and Ray. (Some

uncomfortable scientific facts seem to need rediscovering time and time

again.)

It is odd that the "two Mexican

archaeologists" were not named, but the reference for footnote 5 is an article

by Peter Schmidt titled "La

entrada del hombre a la peninsula de Yucatan." Other sources utilize

Schmidt's study of the Loltun caves to draw conclusions about the chronological

layers.

The aforementioned book The Ice

Age Cave Faunas of North America, page 262, makes this statement:

Stratigraphic

and chronological sequences for the excavated units were established, but

contradictory data from the field notes imply possible mixing of biological and

cultural remains. The sequence as reported is as follows (Schmidt

1988)

1. Levels I through VII are from

the Ceramic stage, but extinct animal remains occur at the bottom of Level

VII.

2. Level VIII

represents the preceramic stage, including some lithic elements and extinct

fauna. The boundary between the Pleistocene or the Holocene may be located

here or at the bottom of Level VII.

Note that the author is utilizing

information provided in Schmidt's report. This statement clarifies that

the extinct animal remains were at the BOTTOM of Level VII, which is the

possible demarcation for the Pleistocene Era. In fact, elsewhere in this

same text, it is asserted that, indeed, Level VII is Pleistocene in

dating:

Loltun

Cave is found at 40m. elevation in the southeastern portion of the state of

Yucatan., 7 m. south of Oxkutzcab. Several publications about the studies

undertaken on the remains from this cave are available, including Hatt and his

collaborators (Hatt et al 1953) and by personnel of the National Institute of

Anthropology and History (Velazquez 1980, Alvarez 1982, Alvarez and Polaco 1982,

Alvarez and Arroyo-Cabrales and

Alvarez 1990, Pollaco et al 1998, see also Chapter 10 of this volume). The

known stratigraphy contains sixteen levels; sediments from levels VII to XVI are

Pleistocene in age. (page 285)

Thanks to the help of Chris Smith,

who provided scans of the text, and John Williams, who translated the text from

Spanish, I was able to obtain the pertinent sections of the Peter Schmidt

text. First, let’s review the portion of the previously quoted Peterson

essay that refers to this research:

“It took until 1977 before that recommendation bore fruit. Two

Mexican archaeologists carried out a project that included a complete survey of

the complex system of subterranean cavities (made by underground water that had

dissolved the subsurface limestone). They also did stratigraphic excavation in

areas in the Loltun complex not previously visited. The pits they excavated

revealed a sequence of 16 layers, which they numbered from the surface downward.

Bones of extinct animals (including mammoth) appear in the lowest layers.

Pottery and other cultural materials were found in levels

VII and above. But in some of those artifact-bearing strata there were horse

bones, even in level II. A radiocarbon date for the beginning of VII turned out

to be around 1800 BC. The pottery fragments above that would place some portions

in the range of at least 900–400 BC and possibly later. The report

on this work concludes with the observation that "something went on here that is

still difficult to explain." Some archaeologists have suggested that the horse

bones were stirred upward from lower to higher levels by the action of tunneling

rodents, but they admit that this explanation is not easy to accept. The

statement has also been made that paleontologists will not be pleased at the

idea that horses survived to such a late date as to be involved with civilized

or near-civilized people whose remains are seen in the ceramic-using

levels. Surprisingly, the Mexican researchers show no awareness of the

horse teeth discovered in 1957 by Carnegie Institution scientists Pollock and

Ray. (Some uncomfortable scientific facts seem to need rediscovering time and

time again.)”

Now here’s the pertinent section

from the Schmidt research, with important sections bolded:

”Critical for

associating human industry with pleistocene fauna is layer VIII, where there is

no ceramic but where lithic tools and many horse remains appear. But

unfortunately there are horse [remains] in layers VII and VI and also a very

small quantity in layer V, all three containing ceramics.

Obviously

there is some disturbance in these layers. Rodents as well as the most common

mammals from the cave stand out in studies of the cave's fauna.

The only

radiocarbon dating published (1805 +- 150) BC was taken using a combined sample

of various pieces of charcoal and belongs to the area of contact between layers

VII and VIII.

The stratigraphic and faunal analyses clearly establish

that the excavated sediments must have accumulated from the Pleistocene era to

the present, with heavy interference at least from layer VII on up. Only layer

VIII remains a possible area of occurrence of both lithic material and

pleistocene bones in a primary context. Unfortunately in neither this layer or

others is there direct association of human tools with the bones, nor are there

fire holes where charcoal or bones were clearly used or worked. The same is true

with layer VII (El Tunel) (p 253).”

[After discussing flora found in

the cave]. The situation in terms of fauna is more complicated. The majority of

the animals discovered are represented since the Pleistocene era, having their

origins in some of the neo-arctic and neotropical fauna. Studying in detail only

the rodents, a sequence of types of vegetation the caves' surroundings was

established that is very similar to that accomplished by means of pollen: layers

before XIII-B, grassland; layers XIII and XII-L, medium jungle; layers XII-K to

VIII, once again grassland; and from VII to I the current vegetation. These

changes were not sudden but rather constitute advances and declines of the

jungle with greater or lesser extension of the grasslands, where large animals

and certain specialized rodents lived.

Once again the end of pleistocene

conditions appears to be situated in the region of layers VIII and VII of the

well "El Toro." Of the four extinct pleistocene species (Mammut americanum,

Canis diris, Tanupolama, and Equus conversidens) and the three whose

distribution receded more to the north (Bison bison, Canis lupus, and Canis

latrans) five did not occur above layer VIII in "El Toro" and layer VII-F in "El

Tunel." [The exceptions are the bison with three problematic examples in layer

VI of "El Toro" and the horse, with 44 fragments in layers VII, VI, and V (all

with ceramics), in "El Toro" and 59 fragments en the subdivisions VII-B and

VII-E in "El Tunel." What is clear is that the presence of the horse Equus

conversidens alone cannot be sufficient to declare a layer as pleistocene in its

entirety, given the long series of combinations of this species with later

materials in the collections of Mercer, Hatt, and others. Something happened

here that is still difficult to explain. Horse bones seem to have formed the

last layer of the Pleistocene or Epi-Pleistocene in various caves, or they must

have been dragged into the caves decades up to millenia later, something that is

difficult to accept given the climatic conditions of the Tropics. If we

postulate a longer survival of the horse than that of other pleistocene animals

to explain this situation, it would have to extend until almost the beginning of

the ceramic epoch, which would not please the paleontologists.

Lithic

Loltun also has not been been very amenable [to exploration]. There are very few

well-defined techniques for dealing with stone fragments and cores; such

techniques have varied widely from the beginning to the end. One of the reasons

may derive from the uselessness of local flint for fine work. In the layers

considered to be pre-ceramic there are very few tools: scrapers, shavers,

knife-scrapers, jagged-edged tools (denticulados), and one sharp-ended tool

(punta), all being of a very reduced size and totaling no more than 11 objects.

Production techniques are limited to marginal finishing using stone chips and

plates as the primary materials.

It may seem excessive the detail with

which we have described the evidence that is so hard to understand about Loltun.

But I believe that it is necessary because of the site's possible importance and

because the findings have become widely known without specifying that the usable

data until now are few and weak. Loltun has been incorporated into general

theories about Mayan archeology and about the origins of humans in Mesoamerica.

Some authors limit themselves to mentioning an association between stone

artifacts and Pleistocene animal bones, for others there is an association [p.

256] with Mammoth bones, and in a summary of the most relevant Mayan archeology

in the last few years the long stratified sequence and the appearance of

ceramics supposedly dated in 1800 BC is indicated. Regarding this last date, we

must emphasize that among the first pots found in layer VII of "El Toro" there

appear some fragments having characteristics of early pottery, but comparisons

with material from Chiapas and from the Swazey complex in Belize have not given

positive results, so the most probable date is Middle Preclassic.

The

preceramic lithic material from Loltun has been tentatively assigned, because of

it primitive and irregular character, to very early stages, before 14,000 BC.

Others place it in the transition between the Pleistocene and Holocene and

compare it with the complex of La Piedra del Coyote in the Guatemalan highlands

and phase I of the Cave of Santa Martha in Chiapas. In this case it would have

an age somewhere around 8000 to 10000 BC. It would be a manifestation of the

Superior Cenolithic or until the Proto-Neolithic, or in other words, the

Archaic.

In view of the evidence I have described, I lean toward the

second possibility, and it is possible that its antiquity could be less, if we

consider the continuity of the lithic of the Preclassic.

There is much

left to do at Loltun. We are sure that there is an association of humans with

pleistocene animals, but we must look in the part that has not yet been

excavated for unmistakable evidence, where the strata have not been disturbed,

where there is direct association of tools and bones, and direct action with the

animals. We lack explicit traces of human visits to the cave as a home, places

of work, or remains of other cultural elements besides only stone chips, and in

the end, remains of prehistoric humans themselves." (pp.

254-55)

Now let’s compare Schmidt’s

statements to the Peterson/Sorenson summary of those statements.

Peterson:

"Pottery

and other cultural materials were found in levels VII and above. But in some of

those artifact-bearing strata there were horse bones, even in level II. A

radiocarbon date for the beginning of VII turned out to be around 1800 BC. The

pottery fragments above that would place some portions in the range of at least

900–400 BC and possibly later.”

Schmidt:

“But

unfortunately there are horse [remains] in layers VII and VI and also a very

small quantity in layer V, all three containing

ceramics.“

My comments: While there is

nothing in this Schdmit reference about horse bones above Level II, Peterson may

have been referencing the earlier Mercer find. However, the horse bones

from the top levels were identified as the modern horse, post-Conquest.

Peterson:

“Some archaeologists have suggested that the horse bones

were stirred upward from lower to higher levels by the action of tunneling

rodents, but they admit that this explanation is not easy to

accept.”

Schmidt:

“Obviously there is some

disturbance in these layers. Rodents as well as the most common mammals from the

cave stand out in studies of the cave's fauna....

The stratigraphic and faunal

analyses clearly establish that the excavated sediments must have accumulated

from the Pleistocene era to the present, with heavy interference at least from

layer VII on up. Only layer VIII remains a possible area of occurrence of both

lithic material and pleistocene bones in a primary

context....

What is

clear is that the presence of the horse Equus conversidens alone cannot be

sufficient to declare a layer as pleistocene in its entirety, given the long

series of combinations of this species with later materials in the collections

of Mercer, Hatt, and others. Something happened here that is still difficult to

explain. Horse bones seem to have formed the last layer of the

Pleistocene or Epi-Pleistocene in various caves, or they must have been dragged

into the caves decades up to millenia later, something that is difficult to

accept given the climatic conditions of the Tropics. If we postulate a longer survival of

the horse than that of other pleistocene animals to explain this situation, it

would have to extend until almost the beginning of the ceramic epoch, which

would not please the paleontologists.”

My first

comment is that the Peterson/Sorenson summary in misleading in that it states

that Schmidt said the possibility that horse bones were stirred upward from

lower levels to higher levels by tunneling rodents is “not easy to

accept”. This is not true. Schmidt accepts that the tunneling

rodents disturbed the layers, as does Mercer.

From page 118 of the Mercer

text:

“Layer 3, one foot eleven inches

to two feet ten inches think, and capped with a solid white bed of pure

ashes.

We soon found that Layer 3 had

been much disturbed, and notably by the burrowing of

animals.”

It should be noted that the

numbers of the layers vary depending upon researcher. Earlier, on page

116, Mercer defined “layer 3” as follows:

”The bottom of Layer 3 marked, as before mentioned, the bottom

line of human interference in the cave earth.”

This seems to roughly

correlate with Schmidt’s level VII.

Rodents

heavily populated this cave and obviously disturbed the layers. What

Schmidt referred to as “difficult to accept” is that the horse bones were

dragged into the caves later, not

that the rodents may have disturbed the remains. Note again:

"

Horse bones seem to have formed the last layer of the Pleistocene or

Epi-Pleistocene in various caves, OR they must have been dragged into the caves

decades up to millenia later, something that is difficult to accept given the

climatic conditions of the Tropics." Schmidt is NOT saying that it would be difficult to

accept that rodent tunneling disrupted the layers of the cave, and hence

relocated the horse bones from the lowest level (the only level in which the

bones were in "primary" context). He is saying that one must EITHER accept that

the horse bones were in the lowest layer and were disturbed, OR they were

dragged in later. The idea that they were dragged in later is

difficult to accept.

The more fundamentally

misleading context of the Peterson/Sorenson statement is that it implies that

Schmidt did not believe that the horse remains dated from the Pleistocene

era. Yet Schmidt made it obvious that he believes that the later layers

were disrupted and that “only layer VIII remains a possible area of occurrence

of both lithic material and pleistocene bones in a primary context.”

This is consistent with the conclusions arrived at in the Ice Age Fauna text

quoted above.

Hun

horse

A

frequently repeated argument among those who insist that the absence of evidence

of the horse dating to the Book of Mormon time periods in Mesoamerica does not

constitute evidence of absence is the following:

Consider

the case of the Huns of central Asia and eastern Europe. They were a nomadic

people for whom horses were a significant part of their power, wealth, and

culture. It has been estimated that each Hun warrior may have owned as many as

ten horses. Thus, during their two-century-long domination of the western

steppes, the Huns must have had hundreds of thousands of horses. Yet, as the

Hungarian researcher Sándor Bökönyi puts it with considerable understatement,

"we know very little of the Huns' horses. It is interesting that not a single

usable horse bone has been found in the territory of the whole empire of the

Huns. This is all the more deplorable as contemporary sources mention these

horses with high appreciation."

58

Accordingly, if Hunnic horse

bones are so rare despite the vast herds of horses that undoubtedly once

inhabited the steppes, why should we expect extensive evidence of the use of

horses in Nephite Mesoamerica—especially considering how limited are the

references to horses in the text of the Book of Mormon?

Daniel Peterson, Matthew

Roper: Ein Heldenleben?

Evidence

contradicting this claim can be found here (provided by Matt Amos from Zion's

Lighthouse Message Board Hun

ZLMB

Hun

Princess Graveyard’s Secret

A Hunnu princess’s

graveyard discovered in summer of 1990 in Mankhan locality of Khovd province has

become the sensation in the world of archeology.

Ever since 1924 when the graveyard of the Hunnu ruler

Modun Shayu filled with riches was discovered, this become only the second time

when the remains of Hun noble was found.

“We were really lucky. The graveyard was not

plundered. Though the wooden cover of the graveyard was demolished the coffin

chamber was well preserved,” says the Khovd archeological expedition head, Prof.

D. Navaan….

Five horse skulls were put on the northern side to

the burial, with one horse head turned towards the coffin. The number 5 was

revered by Huns because of their special reverence for Cygnus Constellation. One

separate horse head probably belonged to the princess’ beloved

horse.

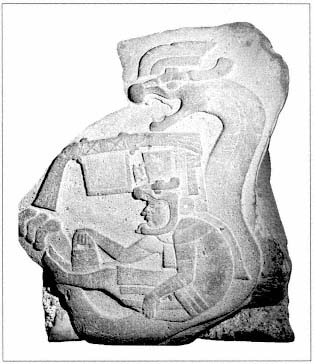

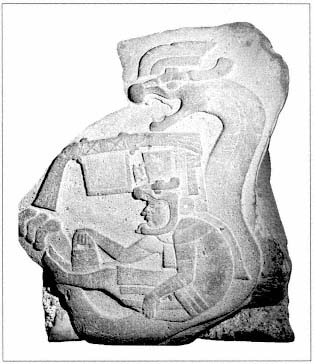

Rock painting from Gobi Alatai province, Khanyn Khad

Mountain Hunnu

princess

Matt

also provided the following citation from Encyclopedia Brittanica:

Mongolian

Huns

In the 4th

century BC the Huns started to migrate westward from the Ordos region. By the

3rd century BC they had reached the Transbaikalia and had begun to enter

Mongolia, which soon became the centre of their empire. Many mounds mark their

progress. Those in the Zidzha Valley lie at the same latitude as the Pazyryk

mounds and were subjected to similar conditions of freezing, which helped

preserve their contents. The richest of the excavated burial sites, however, are

those of Noin Ula, to the north of Ulaanbaatar, on the Selenge River. Like those

at Pazyryk, they included horse burials. The furnishings of one tomb were

especially lavish. The prince for whom it was made must have been in contact

with China, for his coffin was apparently made for him there, as were some of

his possessions buried with him (e.g., a lacquer cup inscribed with the name of

its Chinese maker and dated September 5, AD 13, now in the State Hermitage

Museum). His horse trappings (State Hermitage Museum) are as elaborately

decorated as many of those found at Pazyryk. His saddle was covered with leather

threaded with black and red wool clipped to resemble velvet. The magnificent

textiles in his tomb included a woven wool rug lined with thin leather (State

Hermitage Museum); the centre of the rug depicts combat, of Scytho-Altaic

character, between a griffin and an elk, executed in purple, brown, and white

felt appliqué work. The animals' bodies are outlined in cord and embroidered.

The design on another textile is embroidered in the form of a tiger skin with a

head at each end. The animal's splayed-out body is formed of black and white

embroidered stripes. Other textiles are of Greco-Bactrian and Parthian origin.

In some of the Parthian fragments, Central Asian and Sasanian Persian influences

prevail over Hellenistic ones.

Chris Smith, known as "California Kid" on

various LDS related message boards, shared pertinent information on his blog

regarding this topic. He graciously gave me permission to include that

here.

Book of Mormon defender Mike Ash

recently repeated the

old argument that even though we know that the Huns had plenty of horses, "not a

single usable horse bone has been found in the territory of the whole empire of

the Huns. Based on the fact that other--once thriving--animals have disappeared

(often with very little trace), it is not unreasonable to suggest that the same

thing might have happened with the Nephite 'horse.'"

Ash's claim about

Hun horse bones is unfortunately not accurate.

Here and

here are books that refer casually to Hun horse bone

evidence.

Here is a report on a

Hun horse find in Mongolia in 1990.

Ash's example is also problematic

because bone evidence is not the only evidence we would expect to find in

Mesoamerica if horses had been domesticated there. There have been a large

number of human cultural artifacts relating to horses found in Hunnic lands.

There are a great many

saddles,

harnesses, and whips in their burials and funeral offerings, for example. In

fact, wherever horses have been domesticated, they have always left their mark

on

art

and material culture. That is because horses gave a tremendous military and

economic advantage to the civilizations that mastered them. Yet in Mesoamerica,

although we have a great deal of art, including vast numbers of animal

representations, horses are not depicted. We find no saddles, no bridles, and no

chariot wheels.

Additionally, it should be noted that some historians

have called into question how many horses the Huns actually brought with them

into Europe. The climate and food supplies in Eastern Europe were not as

well-suited to large numbers of horses as the Asian steppes. According to

the

Encyclopedia Brittanica,

[Attila's]

Huns had become a sedentary nation and were no longer the horse nomads of the

earlier days. The Great Hungarian Plain did not offer as much room as the

steppes of Asia for grazing horses, and the Huns were forced to develop an

infantry to supplement their now much smaller cavalry. As one leading

authority has recently said, "When the Huns first appeared on the steppe north

of the Black Sea, they were nomads and most of them may have been mounted

warriors. In Europe, however, they could graze only a fraction of their former

horse power, and their chiefs soon fielded armies which resembled the

sedentary forces of Rome."

So, if there is less evidence of Hun

horses during this period in Europe than we would expect, it may well be because

the Huns of the region actually did not have as large a number of horses as

commonly thought. Indeed,

one

source suggests that Europe's Great Hungarian plain could have supported no

more than 20,000.

And finally, it's worth adding that the period of Hun

rule was quite short compared to the several-thousand-year lacuna of horse

evidence in the Americas from the generally-accepted Paleolithic extinction date

to the time of alleged domestication by Book of Mormon peoples. Even if the Hun

period had been a true lacuna-- which it is not-- it wouldn't really have been

comparable to the situation in the

Americas.

http://chriscarrollsmith.blogspot.com/2010/03/hun-horse-bones-and-book-of-mormon.html

Wisconsin Spencer Lake Horse

Skull

Daniel Peterson, in the

FAIR online video The Book of Mormon and Horses, made the following

statements:

“There have also been some horse bones that have been radiocarbon dated

to about the time of Christ that were found in the upper mid-west in the United

States.”

“Preliminary reports seem to indicate that those horse bones do date, in

fact, to Book of Mormon times.”

Daniel

Peterson horse claim

filmed in January 2006

This can only be a reference to the Spencer Lake horse skull.

(Additional evidence that this is what Dr. Peterson was referencing can be found

in this thread from Mormon Apologetics Discussion Board:

MAD

discussion Spencer Lake)

It has been long rumored within LDS internet circles that the horse

skull was in the process of being radiocarbon dated, and despite claims of a

hoax by some, would provide just the evidence Book of Mormon believers

needed. The radiocarbon dating was being conducted by Dr. Stephen

Jones, a professor at BYU, as is Dr. Peterson. Before sharing the results

of those tests, a brief review of the history of this find is in

order.

There

Were No Ancient Vikings in Wisconsin?

Prank at Spencer Lake

Mounds

By K. Kris Hirst,

About.com

Spencer

Lake Hoax

One extremely persistent rumor in alternative archaeological circles is

that there is evidence--suppressed evidence--that the Native American mounds of

Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa were built by Vikings. To support this premise,

oddly shaped glacial erratics are thought to be "Viking mooring stones," various

"rune

stones" of very dubious origin are cited, and, as in the case of this story,

there are rumors of horse skeletons which were found in mounds--and the evidence

suppressed. One of the funniest stories associated with these Viking legends

has to do with the Spencer Lake Mound in extreme northwest Wisconsin. There was,

undeniably, a horse skull found in Spencer Lake Mound. How it got there is a

tale worth telling.

Spencer Lake Mound and the

Clam River Focus

The Spencer Lake Mound is a large round, hemispherical burial mound, the

largest of several mounds located

on terraces near the shore of Spencer Lake, Burnett County, Wisconsin. During

the 1935 and 1936 excavations by the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee,

excavators found a total of 58 separate secondary burials, accounting for a

total of at least 182 individuals. Artifacts recovered from the site included

triangular arrow points, a shaft straightener, red ochre, a hearth, and a few

sherds of Clam River pottery, which is part of the BlackDuck ceramic group.

Birchbark baskets and the claws and skin of a beaver were recovered from the

burials.

The Clam River Focus was

established by archaeologist Will

McKern, and besides Spencer Lake Mound includes the Clam Lake Mound Group.

The people who built and used these mounds to bury their dead lived during the

end of the Middle Woodland period, ca 500-700 AD, well before the historic

period--and, for those trans-oceanic Viking aficionados, a good 300-500 years

before the Viking colony in Newfoundland called L'Anse aux

Meadows site was occupied.

How the Story

Began

During the summers of 1935 and 1936, the University of Wisconsin

excavated Spencer Lake Mound. The principal investigators were Ralph Linton and

W. C. McKern; their staff of students included A.C.

Spaulding, George Quimby, David Stout, and Joffre Coe--all destined to

become pretty famous archaeologists in their own rights. It was in the fall of

1936, probably, when a young college student signed up for a beginning

anthropology course taught by Ralph Linton. The young man, who is known in this

story only as Mr. P., had been an avid artifact hunter while growing up in

northwestern Wisconsin. Conversing with his classmates in 1936, Mr. P.

discovered that excavations at the Spencer Lake Mound the previous summer had

revealed an astonishing artifact: a horse's skull buried deep within the mound.

Mr. P's

Confession

This was quite a shock to Mr. P. After gathering all of his available

courage, he went into Linton's office and confessed that in 1928, the then-teen

aged Mr. P. and a buddy had spent an afternoon pot-hunting the Spencer Lake

Mound.

The boys dug a sizeable hole, consuming the better part of a hot

afternoon, without encountering any kind of a recognizable feature. They were

about to backfill the opening when one of them suggested that they bury a

horse's skull that lay along the edge of a nearby field a short distance away.

This seemed like a brilliant suggestion to the undisciplined minds of the boys,

so the skull was retrieved and carefully laid in an oriented position at the

bottom of the excavation before backfilling commenced. Anticipation of the

probable results of this piece of mischief somehow eased the monotony of the

backfilling, and the miscreants mutually agreed that in about two hundred years

some archaeologist would dig up the skull and conclude that he had found

something really worthwhile [from Mr. P., Wisconsin Archeologist 45(2):120

(1964)].

Linton found the story amusing, apparently, and a mightily relieved Mr.

P. went off onto a career of his own, outside of archaeology. But, either Linton

didn't tell McKern about the prank or he did tell McKern but McKern didn't

believe him. For whatever reason, over the next 25 years or so, at least three

publications--and probably a few others--described the Spencer Lake Mound as

containing an in situ horse skull.

In 1962, Mr. P., by then a college professor but still with an

avocational interest in archaeology, dropped into the office of Robert

Ritzenthaler at Milwaukee Public Museum, when the first

major monograph for the Clam River Focus (including the Spencer Lake Mound) was

being prepared. Mr. P. told Ritzenthaler about his youthful escapade, and

he was quite contrite

about it and agreed to prepare a statement of the facts as best he remembered

them, after 34 years. A copy of this was sent to McKern, who responded with a

statement to the effect that he was convinced that the skull he excavated was

not the planted one, but as there was reasonable doubt, he would make some

revisions [in the monograph] and suggested that his statement be published. Mr.

P., however, requested that neither his statement nor McKern's be published, a

request that was honored, until the Griffin review. [Ritzenthaler, Wisconsin

Archeologist 45(2):115-116 (1964)].

James B. Griffin Exposes the

Prank

Enter James B.

Griffin, undeniably doyen of archaeology for the American northeast. In

1964, Griffin wrote a review of the Clam River Focus monograph, and noted that

despite the previous publication of a horse skull in Spencer Lake Mound, there

was no mention of it in the book. And, so, finally, notwithstanding the high

level of embarrassment suffered by Mr. P., with an academic career of his own to

maintain, notes by Mr. P., W.

C. McKern, and Robert Ritzenthaler describing the story above were published

in the Wisconsin Archeologist, and the situation

was resolved. Further evidence (beyond Mr. P.'s complete lack of motive for

making this story up) was provided by Walter Pelzer, mammologist at the museum

in those days, who looked at the skull and identified it as a western mustang, a

horse imported for use on Wisconsin farms in the early 20th century. Pelzer also

spotted rodent gnawing on all planes of the skull that suggested to him that it

had been exposed to the weather for a while before being buried. Radiocarbon

dates of the charcoal recovered from the mound provided a use date for the mound

between circa 500-1000 AD.

At no point in these proceedings has any archaeologist ever believed the

presence of the horse indicated early Viking presence in the American Midwest.

The horse skull only suggested to McKern and others that the Clam River Focus

sites (of which Spencer Lake Mound is one) dated to the early historic period

(i.e., 1700s). But, because there are publications in dusty library stacks

saying there was a horse skull in Spencer Lake Mound, the rumors continue to

persist, I suppose on the principle that if it's in print it must be true. But

no! despite what you may have heard, as far as the evidence shows, the only

Viking presence in the Americas was a failed 11th century colony in Newfoundland

called l'Anse aux

Meadows.

McKern, W. C.

1964 The Spencer Lake horse skull,

Response to Mr. P.'s letter of June 28, 1963. Wisconsin Archeologist

45(2):118-120

1929 Wisconsin archeology in light of recent finds in

other areas. Wisconsin Archeologist 20(1):1-5.

1942 The first

settlers of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Magazine of History 26(2):153-169

1963 The Clam River Focus. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in

Anthropology No. 9. Milwaukee.

Mr. P.

1964 A Burnett County

hoax. Wisconsin Archeologist 45(2):120-121

Ritzenthaler, Robert

1964 The riddle of the Spencer Lake horse skull. Wisconsin

Archeologist 45(2):115-117

1966 Radiocarbon dates for Clam River

Focus. Wisconsin Archeologist 47(4):219-220

Having an actual confession was no deterrent to those determined to find

evidence of the horse during Book of Mormon times, and their determination

resulted in the offer of Steve Jones to have the skull radiocarbon dated.

There have long been rumors that when this carbon dating was revealed, it would

demonstrate that the horse was, indeed, from Book of Mormon time periods, as Dr.

Peterson’s statement above demonstrates..s.

In reality, the radiocarbon dating results were in long ago. In